Isadore and Tina Henry eat at Michelle's Country Diner twice a week. Hear their thoughts on what makes it so special and why they believe it is changing Baldwin Hills for the better.

For Michelle Allaire, 20 years of owning S&W Diner in Culver City was not enough for her restauranteur interests.

So when the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza Mall asked her to open another location in a space then being used as a Fatburger, Allaire made it her own.

Her creation: Michelle’s Country Diner, an all-day restaurant serving up anything from burgers to breakfast, and doing so in a basic yet refined space in the center of Baldwin Hills.

“I wanted to give the community something beautiful, because I wanted to put my love into it and into the environment,” Allaire said. “I want to give this community the most beautiful restaurant they have had access to.”

Upon walking into Michelle’s, the stereotypes of a 1950s red-booth laden diner are immediately quashed. Rather, the diner takes shape of a home kitchen: gray spindle chairs, low-hanging chandeliers, and glass cabinets with small vases and sculptures inside them stand out. For Allaire, the goal for the restaurant bearing her name fits this exact vision: home.

“People who know me personally come in here and say it looks exactly like my own home,” Allaire said. “It’s a warm, comfortable feeling, and that’s what I want for this community.”

For the community, a sit-down restaurant like Michelle’s is a new concept.

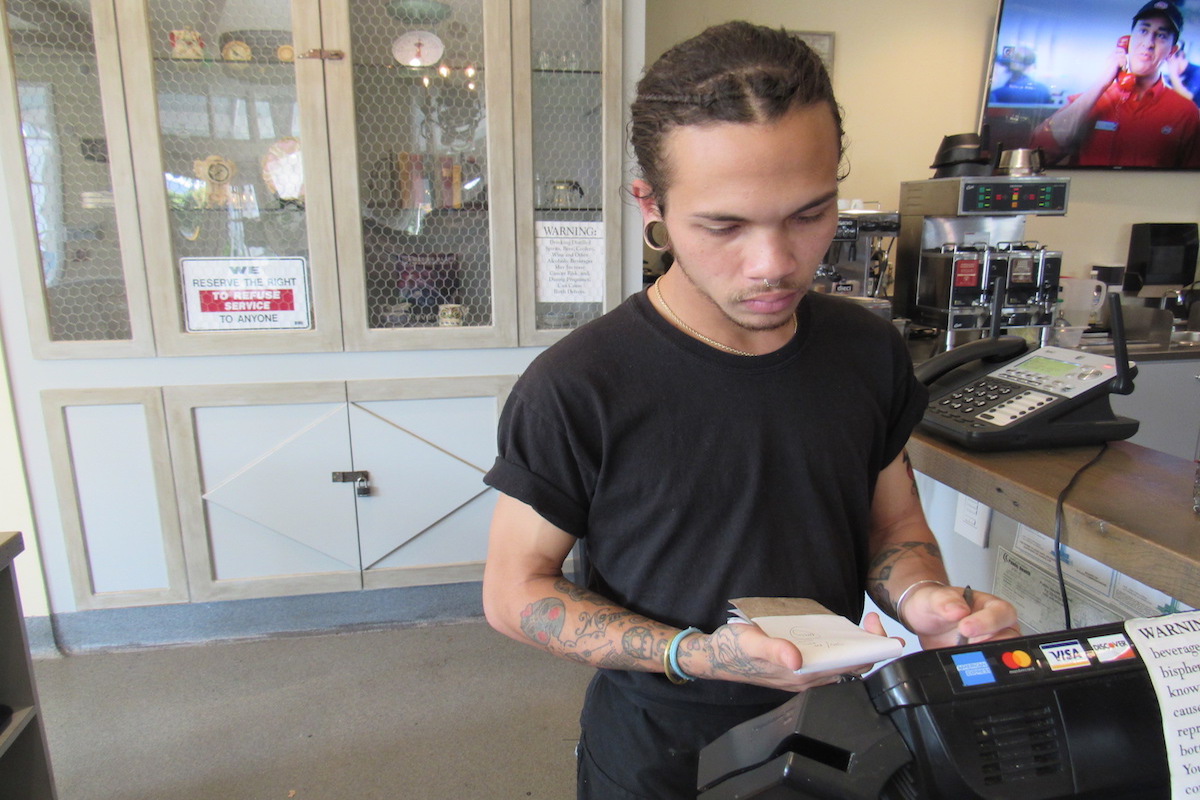

“We are raising the bar for food in this area…there is not a lot of good food around here, especially for breakfast,” Nile Villa, waiter, said.” “It’s mostly just fast-food.”

Villa, 22, has worked at Michelle’s since the day it opened in September 2016. He lives within a mile from the restaurant, hitting on one of Allaire’s main goals: to only hire workers from the community.

“The neighborhood is very protective of itself, so giving kids the opportunity to work, stay off the street, and make an income is helpful,” Allaire said. “They ride their bicycles and skateboards to work- it just helps add a local element to it all.”

Michelle’s prides itself on the relationships amongst staff members: even the staff shirts say “squad” on the back. Friendly teasing and constant laughter fill the space, which makes business seem smooth.

“It’s like I come here and am working with friends, we are all so compatible with one another,” Julian Koprowski, busser, said.

However, the restaurant’s relationship with the community surrounding it has not always been as compatible, with Allaire’s race playing a key role.

“In the first nine months guests would walk in and immediately ask if this was a black-owned business,” Allaire said. “When they found out I was white, they would walk out immediately.”

For those that would choose to stay, the race of the cooks making their food was the next target.

“At the beginning guests would tell me they only wanted to eat food if it was cooked by a black person,” Allaire said. “All of our line cooks are white, so I hired a black cook and put him right in the window so everyone could see, and the customers were so happy.”

This racialized line of thought stems from a community desire to keep as much as possible insulated within the African-American community, according to Soluna Godeau, a waitress at Michelle’s who also lives within a mile of the restaurant.

“People in the neighborhood have issues with white people cooking because they think that only if a black person is doing something is it being done in the ‘right way,’” Godeau said.

The menu is designed around a relaxed elegance; standard fare such as burgers, sandwiches, and all-day breakfast options, but served in Allaire’s “homey” environment.

But like Allaire and her cooks, the menu was not immune to the community’s backlash, with the term “country” being chastised for not emulating a Southern country experience.

“We had to add fried chicken, yams, real greens, bread pudding, and ribs to the menu to please the community around us,” Allaire said. “Even though there are plenty of fried chicken restaurants around us here in Baldwin Hills, our clientele made it loud and clear that they wanted soul food.”

Now, fried chicken is Michelle’s most popular item.

“I absolutely love the fried chicken here,” George Burkhardt, 63, said. “I think it is prepared well and all, but what I really like is that I can have it with some eggs or pancakes at night. That’s the beauty of having a diner here.”

No matter how the community grows, Allaire wants Michelle’s to continue to make a mark as a staple.

“Police eat here, the mayor eats here, and we’re all on a first name basis,” Allaire said. “That’s the type of relationship I want.”

Allaire has personally taken an initiative to immerse herself in Baldwin Hills life by baking cookies for police for Christmas and speaking at a female business owners event at the YMCA.

But she prefers that the credit be shared amongst the “squad” that she works with each day.

“As a team, as a squad, our intention is just to be involved in this community and help it grow,” Allaire said. “That’s what Michelle’s Country Diner is all about.”