East 1st St. from above

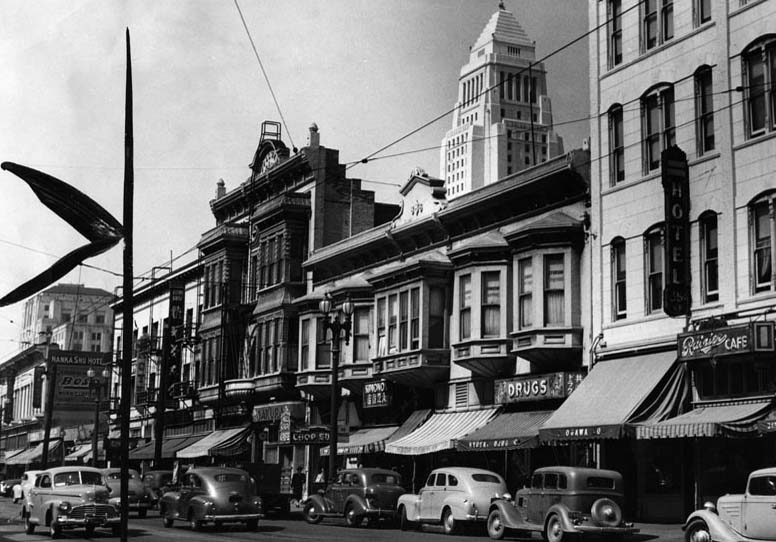

Aerial photo of a very busy East 1st St. in the 1940s.

In Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, East 1st street is home to some of the oldest buildings in the city—some buildings dating back as far as the 1890’s. The road to today was not an easy one, as there was once a time when many of the buildings were slated for destruction. Learn the story of how some of L.A.’s oldest buildings have been kept standing.

Aerial photo of a very busy East 1st St. in the 1940s.

An East 1st St. store has visitors before the war in 1939.

East 1st street laid empty shortly after Japanese internment began.

East 1st street, empty after Japanese American internment.

Is what Little Tokyo was called during the war as African Americans moved in.

Used only as storage for Japanese American evacuees during WWII.

Explore the history of some of Los Angeles' oldest buildings.

LOS ANGELES, Calif.—Thirteen structures line the sidewalk between 120 Judge John Aiso St. and 369 East 1st St. in the Little Tokyo Historic District. The inconspicuous dozen and one are home to more than just small gift shops and eateries—they are each home to about a century of history.

With at least one building dating back to the 1890's, the north side of East 1st Street is the site of some of the city's oldest buildings—but the rode to todays was not an easy one. Before being placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986, the only thing that stood between these structures and redevelopment was Little Tokyo's dedicated community leaders.In the early 1950's, the construction of the Parker Center (a police administration building) knocked out housing for nearly 1,000 Little Tokyo residents and much of the area's commercial frontage. A decade later, a plan to widen East 1st St. and expand the Civic Center into Little Tokyo forced community leaders to take action.

Community leaders responded with redevelopment proposals that focused on urban renewal and preservation—which ultimately led to the Little Tokyo Redevelopment Project that reshaped a lot of the area over through the 1970s and 1980s.

Community leaders like Brian Kito, owner of Fugetsu-Do Bakery and President of the Little Tokyo Public Safety Association, remember a time in the 1980s when the threat of eminent domain and redevelopment loomed over the area.

"The city wanted to take this entire block," said Kito in an interview. "They wanted to widen the street by 20 feet."

Fugetsu-Do, Brian Kito's family bakery that had been a staple of the community since opening in 1903, laid in the path of a redevelopment plan proposed by the city. So sitting idly by was not an option.

"I started fighting for the block," said Kito. "The good thing was the property owners agreed with me, and the business owners agreed with me—so we had a consolidated front of property owners and business owners to fight the city... So I took it to the city hall and fought."

After a few years of fighting, Kito and the other community leaders won—earning a spot for twelve of the thirteen structures on the National Register of Historic Places. Which of the thirteen did not make the list?

"The building that I'm in at Fugetsu-Do is the only non-historic building on the block because it was rebuilt in 1956," said Kito. "All the other buildings here are over a century old."

But why did they focus on protecting those structures in particular? One reason was because of their historic significance as a staging area for the evacuation of Japanese Americans before they were forced off to internment camps during World War II. But there was also a more strategic reason involved.

"In order to stop them, we looked at the Nishi (Hongwanji) building and the church at the corner," explained Kito. "We grabbed that building as an anchor, because if you can't tear that building down, there's no use in tearing down the rest of the block."

As a National Historic Place, the structures are now safe from city redevelopment. But just because those buildings are safe from redevelopment, doesn't mean that every form of change will be thrown out the window.

"They cannot be altered on the exterior, just the interior," said Michael Okamura, President of the Little Tokyo Historic Society, in an interview. "With the dynamics of little Tokyo changing rapidly now, we're seeing a number of buildings are being rehabilitated in the interior."

One such example of that is Far Bar on 347 East 1st St. that was heavily damaged in the Northridge earthquake in 1994, forcing it to close its doors. A large restoration effort brought the building the building back to life, helping it reopen in 2005.

Another example you'll find at 331 to 335 East 1st St. in what was once the Mikado hotel in 1914. The new owners are turning the former residential space into micro-lofts. They have been working with the LTHS to try to replicate the original façade you might have seen at the hotel during its heyday.

Okamura feels part of the Little Tokyo Historic Society's challenge moving forward is helping the community hold onto the history that makes it unique, while helping it embrace the future and continue to grow and thrive.

"We take great passion in the neighborhood because it's been around for so long," said Okamura. "We don’t want to live in the past, we don't want to be stuck in the past—so we need to move forward."

Whatever the future holds for Little Tokyo, those worried about the area losing its historic charm need not do so, as it seems there will always be people trying to honor the area's past.

"I'm involved in Little Tokyo to honor my grandparents and my parents and all the forbearers before," said Okamura. "What they built is so important, and is still very important today."

Take a look back at key dates in the Little Tokyo's past.