Fleeing gang violence and economic insecurity, Walter Ponce was 17 years old when he left his native Honduras for a “better life” in the United States. He crossed a total of three borders, aboard countless buses and the infamous cargo train “La Bestia”, until finally reaching the neighborhood of MacArthur Park in Los Angeles.

“We suffered along the way,” he said. “We would walk for days without eating anything, trusting in our smugglers to not leave us behind.”

Ponce is one of many Central American nationals who’s made the long haul through the Southern border to MacArthur Park. With an estimated 814,000 undocumented immigrants, Los Angeles County has the highest concentration of undocumented residents in California. MacArthur Park is one of the county’s largest enclaves for Latino immigrants, with more than half of its population from Mexico and El Salvador.

Jose Gardea, a Los Angeles historian and former L.A. City Council candidate, said historical records show that MacArthur Park has been an entry point for immigrant communities since the early ‘50s.

“MacArthur Park and the Westlake area has always lent itself to higher-density housing,” he said. “It’s always been an area where the housing is cheaper. Immigrants go where they can afford to live.”

But Gardea notes that the established immigrant community in MacArthur Park has also attracted new arrivals throughout the decades.

“Central American advocacy organizations like the Central American Refugee Center, CARECEN, Asosal, and other neutral aid groups opened their offices in the area when large waves of immigrants were coming in the ‘70s,” he said. “Immigrants tend to go to areas where there are fellow immigrants because there’s safety in numbers.”

In addition to the advocacy groups immigrants find in the area, MacArthur Park’s support system is comprised of churches, recreational programs and Hispanic businesses where Latino immigrants are not considered “the other”, but are instead one and the same with their compatriots.

Located less than a mile north from the park, the Precious Blood Catholic Church has serviced the MacArthur Park community since its founding in 1923. Aside from providing mass services in Tagalog, Spanish and English, the church contributes to the community with financial help to its members and food. They also work with advocacy organizations to inform immigrants on their rights.

“We worked with an organization called One LA-IAF. They were trying to help immigrants improve their renting rights for apartments through one of their new programs,” said Patricia Siguenza, a supervisor at the church. “As immigrants who are undocumented, many of them are scared to speak out. But during our masses, we were able to get many of them to sign up anonymously and start fighting for their rights.”

Siguenza said that with the Trump administration coming into office in January, the church has recently started to focus on easing the qualms of its members.

“I already had a person come here panicking because of the presidential election and the negative impact it may have on immigrants like herself,” she said. “We’ve had several people come here asking to speak to the priest about their futures under a Donald Trump administration. I know that there's a lot of people who are worried and are going to want to come here to discuss their feelings.”

While the church provides a safe space for immigrants to express themselves, the recreational and academic programs located at the MacArthur Park Community Center lend the assistance some families need for their children.

For $65 a month per child, the park’s facilitators host an after-school program to help elementary school students with their homework. The program, which started with nine children in 2009, now assists 38 children.

“Some of our children have just arrived to the country, so we have bilingual tutors to help them with their homework,” said Andy Ho, the recreation facility director. “Some of them don't even know how to read to be honest, but we do the best we can to help them.”

With the support of nonprofits and local officials like Aztecs Rising, the Gilbert Cedillo office, the Daniel Hernandez Foundation and others, the center also organizes seasonal events for their youth. Some of these include the park’s Halloween Festival, Fishing Derby and Gilbert Cedillo’s Winter Holiday event. They are free to the community and held in English and Spanish.

“Our programs and events serve as a melting pot for the Central American community of MacArthur Park,” Ho said. “They feel comfortable here because we help them assimilate to the United States, but at the same time they are surrounded by their own people.”

Living in a neighborhood like MacArthur Park where more than 73 percent of the population is Latino, Central American immigrants have an added perk: the businesses in the area provide products and services in accordance to their tastes.

Since its inception in 1997, Bibi’s Cafe has delivered Honduran specialties like Baleadas, a flour tortilla filled with fried beans and Pastelitos, cakes filled with chicken.

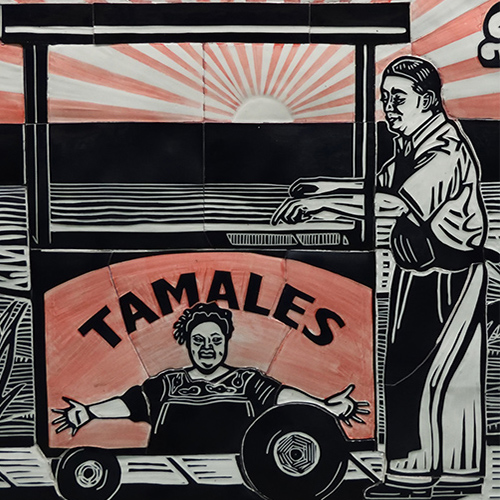

Other restaurants like Paseo Chapin have prepared Guatemalan cuisine like Fiambre, a chilled salad with over 50 ingredients, and tamales for decades.

Meanwhile barber shops like Park Plaza, which employs all Hispanic barbers, prides itself on the quality of their service and being able to understand the specific hairstyles their Central American customers ask for. Haircuts start at $15.

“I think our customers trust us because we speak their language,” said Jose Ledezma, a barber and manager at Park Plaza. “They trust we’ll get the details right.”

In a country where many refer to immigrants as the “minority”, the “other” or “different” from the norm, MacArthur Park has become a democratic home for the newcomer.

“I think we should be celebrating that we have a neighborhood like MacArthur Park because it is very much an entry point for new communities coming into our city,” Gardea said. But as we celebrate, we should be working harder to make sure it continues to be a welcoming space where the housing is healthy, the infrastructure is strong and the transportation options exist.”