Street vendors hindered by law find

support in local community

MacArthur Park's approach to handling the city's legal limbo on unlicensed sidewalk merchants

Behind a frail cart of assorted herbs and various foreign medicines, Blanca, 69, sat back in her chair and tried to barter her goods to the crowds of people strolling alongside busy Alvarado St.

“I’ve been doing this for about 40 years now,” Blanca said solemnly.

“I used to work at a different store, but I decided to sell my own stuff. I can get the same thing doing this.”

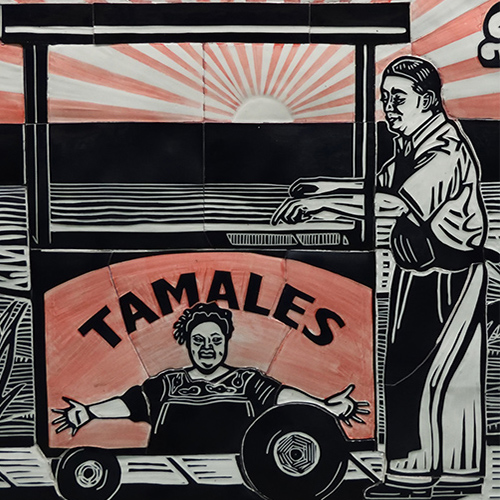

The “this” that Blanca is referring to is something that Angelenos experience every day. An informal economy of epic proportions. An underground network that’s profoundly impacting much of the city’s political, economic, and social circles: sidewalk-street vendors.

These dealers hawk everything – from hygienic products to clothes, from fake IDs to fruits in a truck, and practically everything in between.

According to the Los Angeles Bureau of Street Services, Blanca is just one of roughly 50,000 other street vendors operating on the sidewalks in the city, a figure that continues to rise with no signs of slowing down.

However, these sidewalk merchants are operating along a legal limbo: Los Angeles is one of the only major U.S. cities that doesn’t allow street vending without a permit.

In 1996, city officials adopted the Special Sidewalk Vending District Ordinance to allow for vending in specific commercial districts. But since the process for establishing a vending zone was surrounded by too much red tape, they were quickly forced to abandon the ordinance.

To make matters worse, after City Council rescinded its short-lived pilot permit program, they never created any new formal process to allow for street sellers to attain a permit, rendering every vendor after illegal.

The only commercial district in the entire city that was established under the original ordinance was, oddly enough, MacArthur Park. And 20 years after the fall of the ordinance, its legacy as the epicenter for this activity still lingers on.

In the Westlake/MacArthur Park area, what many believe to be the hub of sidewalk merchants, roughly over 1,000 vendors compete to sell their products. Here, rules are loosely enforced against the pedaling community, if ever at all.

“It’s here to stay. It’s not going anywhere,” said Frank Garcia, a Senior Lead Officer for the LAPD Rampart Community Station.

“Though it is illegal, as long as they follow the rules we put out for them, we don’t really care much. We understand they’re just trying to make an honest living.”

RULE #1

The MTA Bus Ramp must remain clear at all times throughout the day.

RULE #2

Vendors cannot sell near a fire hydrant and must remain 15 feet away.

RULE #3

Neither porn nor sexually explicit content can be sold or publicly visible.

RULE #4

For health reasons, no live animals of any kind can be sold to anyone.

RULE #5

Vendors cannot sell their goods in front of business with similar products.

Many of the vendors in MacArthur Park are undocumented immigrants who cannot legally secure a job elsewhere because of their citizenship status.

For them, this is oftentimes their only source of income.

“The truth is, we have to find whatever we can to put food on the table,” lamented Francisco, a 43-year-old selling cosmetics and household appliances.

Ana, 34, a single mother of two children, one of them disabled, handles counterfeited brand-name clothes and said her business is the only place where she can make money to provide for her family.

“I can’t have a stable job because [my kid] needs me, and I have to take care of him.”

Street vendors make on average $204 a week, or roughly $10,098 a year in revenue, according to findings by the UCLA Street Vendor Project. In Los Angeles, where the median annual income hovers around $56,000, a vendor’s salary figures grossly under the poverty line.

Though many of them struggle to stay afloat financially, research indicates that they are positively impacting Los Angeles – and on a massive scale.

According to an Economic Roundtable Report, expenditures by an estimated 50,000 street vendors generates $517 million each year in local economic stimulus and, to meet their demand, also sustains an estimated 5,234 jobs.

The research also concluded that businesses located near the vendors were more likely to see job growth and higher levels of employment.

Despite these findings, many brick and mortar businesses harbor deep sentiments against the street vending community.

These critics argue that vendors threaten the economic livelihood of established businesses since they can offer lower prices, especially smaller ones.

After profits fell 23% last year for the infamous Langer’s Deli next to MacArthur Park, Norm Langer, the current owner, took to the L.A. Times to vent his frustrations.

Langer described the scene on Alvarado St. as a “gauntlet and unsightly mess” that drove off customers from his restaurant, and he believes the reason for the losses is largely a cause of the unlicensed street vendors.

Other opponents claim that peddlers enjoy a financial advantage since they don’t pay rent, taxes, or have employees on a payroll.

This conflict has generated a heated city-wide debate between the advocates who want to legalize street vending and those who don’t.

As for MacArthur Park, though, Councilman Gilbert Cedillo, the City Council Representative for District 1, is in full support of the sidewalk selling community.

“Our opinion is that we’re in favor of it. We support it,” said Fredy Ceja, the Communications Director for Councilman Cedillo.

“But we do understand that there needs to be laws and regulations to control it.”

Ceja went on to later note that they are working with the County Office, the Sheriff’s Department, and LAPD officials to alleviate the issues surrounding street vending.

The proposal put forward by Councilman Cedillo and his staff would designate the Metro Plaza on Alvarado St. as a safe zone for all sidewalk vendors to sell, thereby restricting any vending activity outside of the permitted area.

The plaza will be patrolled by law enforcement officers from various agencies, and the beta project is expected to be in full effect by the end of December this year.

Until the City of Los Angeles makes any progress in establishing a set of practical, enforceable rules on street vending, it seems as if Langer’s and other businesses in the MacArthur Park area will have to deal with the vendors, whether they like it or not.