Growing up Chinese on the American basketball court

How athletics shaped the Chinese American youth experience in 1930s California.

It wasn't until the 1930s, forty years after the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed, that the ways in which the exclusionary legislation would affect the future of California's Chinese American population became apparent.

In a climate of deep racial and ethnic segregation across the state, the first class of second generation Chinese American young people was coming of age. Caught uniquely between their parents' generation and an American youth culture that surrounded but excluded them, Chinese American teenagers built a culture that was unique to their time, their ethnicity, and their surroundings.

According to Kathleen Yep, professor of Asian American studies at Pitzer College, young Chinese Americans growing up in the thirties and forties were forced to navigate the complex racial, social, and gendered landscape of California.

"Women in general were fighting for the right to vote, people are living under Jim Crow Laws, you were in the midst of the Great Depression. For specifically the Asian and Asian American community, under the Chinese Exclusion Act, there were rampant restrictions on employment and housing. So that’s the terrain under which these youth were emerging as the first second generation of Chinese Americans."

In learning to navigate a landscape that was neither racially nor economically kind to working class Asian families, Chinese American youths turned to each other for support and community.

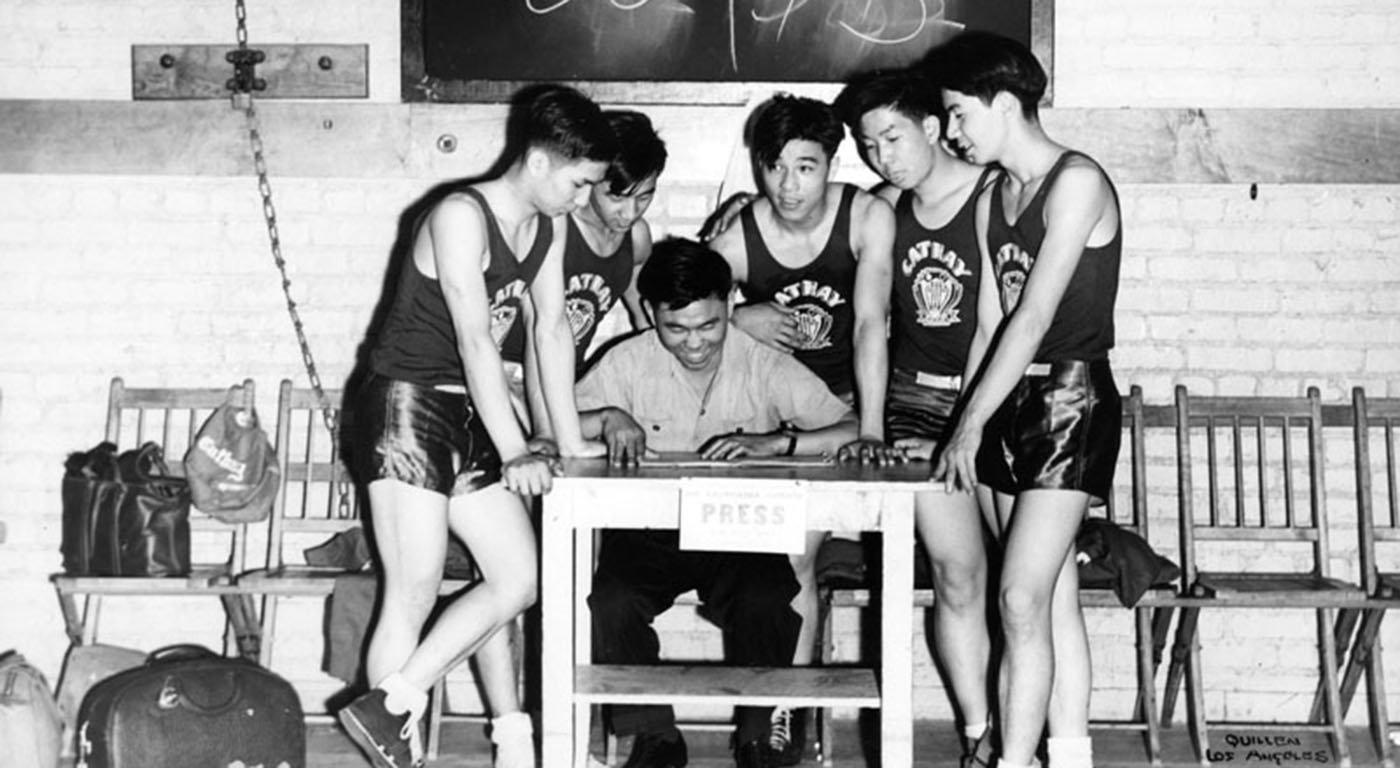

More specifically, they formed teams. Basketball teams, then marching bands and drum corps, and tennis teams.

"They were part of a larger movement of youth groups that were sprouting up across the nation during this period. Partly as a result of the Exclusion Act, the percentage of the Chinese population that was native-born to America was growing at this time," William Gow, a doctoral candidate in ethnic studies at UC Berkeley explained.

This demographic shift created a need for youth spaces that were ethnographically specific, Gow said. It was in these spaces that this first second generation came into their own. There, they could form an identity and community that was unique to their particular experience.

"Sports are often seen as this meritocratic space in which you don’t see race or gender or class. You just play and whoever plays the best is the winner. But actually what these basketball players showed is the sport was deeply embedded in the context of segregation. It was imbued with meanings of race, gender, and class," Yep said.

Basketball, Yep said, has a relatively low start-up cost and an easier learning curve than other sports. It allows a lot of people to play in a relatively small space, which is important to communities with limited access.

Chinese American basketball players developed a very particular playing style that catered to their physical strengths. They were quick and wily, Yep said, and came to be known for causing turnovers and scoring quickly. They were formidable.

One all-girls team, the Mei Wah, was formed as a basketball team in Los Angeles’s Chinatown in 1931. Their model spread quickly across California and by 1935, the San Francisco Mei Wah had won the San Francisco Rec League Championship.

As the Mei Wah grew in number and age, they also formed marching bands and drum corps, performing in local parades and competing in regional competitions.

"A lot of youths at this time wrote about seeing themselves as American and in Los Angeles, they went to high school outside the Chinese American community. But they're at this period of time when other people don’t necessarily see them as American," Gow said.

Youth groups like the Mei Wah, the Lowa, the Waku Auxillary, and other teams linked with city parks and local schools were positioned squarely at the intersection of their nationalities. They were so good at what they did that they forced the white teams they competed against to pay attention to their unique, Chinese-influenced approach to quintessential American pastimes.

"People knew of certain players. In the women's basketball scene in the 1930s, there were players that were considered to be dominant, almost like the Michael Jordan of that generation who played multiple sports and were really strong in a specific skill," Yep said.

According to Yep, reaction to the mass adoption of team sports from the generation that raised them was mixed.

"Some parents felt that, yes, as a strategy, they should understand and occupy a particular Chinese American space. But other parents were concerned about the risk of their children traveling across California for basketball tournaments or leaving Chinatown and being exposed to the outside community. There were very different philosophies and strategies within that one generation,"" Yep said.

No matter their parents' opinion, Chinese American youth cultural blossomed during this time.

"It was expansive, textured, and diverse. Young men and women from different class backgrounds found different ways of expressing their masculinities and femininities, whether it was through basketball or music. They ran marathons in San Francisco, they had football and tennis teams. They put on fashion shows. There was a huge music scene," Yep said, "It was a unique time of movement as expression."

Faced with a time of distinct in-betweeness, American-born Chinese resisted an "either-or" identity and created an exciting one all their own that straddled the boundary between Chinatown and the outside world that wanted to keep them out, but couldn't.