There’s something in the air in downtown Los Angeles, and it’s a sign of something that’s on the streets, too. Streams of urine and piles of feces dotting the downtown sidewalks too often have the neighborhood looking—and smelling—more like a sewer than a cosmopolitan city center.

“This is everyday,” said DePriest Williams, a city maintenance worker, as his partner power-washed a spray of diarrhea in the doorway of a Spring Street storefront. “It’s dog and it’s human, too. That there is human.”

Though the issue may seem like nothing more than an especially repulsive annoyance, human and animal waste in the streets can actually pose serious risks to public health.

While urine is relatively harmless, feces contain a hoard of potentially dangerous bacteria. Dog feces can spread hookworms and roundworms, as well as other bacterial infections. Human excreta can transmit many infectious diseases, including cholera, hepatitis, polio and typhoid, according to the Center for Disease Control.

“Human feces can be an issue because that’s how we spread a lot of infection,” said Gregory Stevens, associate professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

While sidewalks in the more commercial areas are often cleaned daily, traveling to the outskirts of downtown and toward skid row, sanitation conditions worsen.

Skid row has often been subject to public health concerns attributed to unsanitary living conditions. In 2012, the Public Health Department found the City of Los Angeles in violation of county health code after an inspection in which 90 piles of human waste were found in a 10-block radius encompassing skid row. The conditions there have been linked to outbreaks of tuberculosis, meningitis and staph infections, all of which can be fatal.

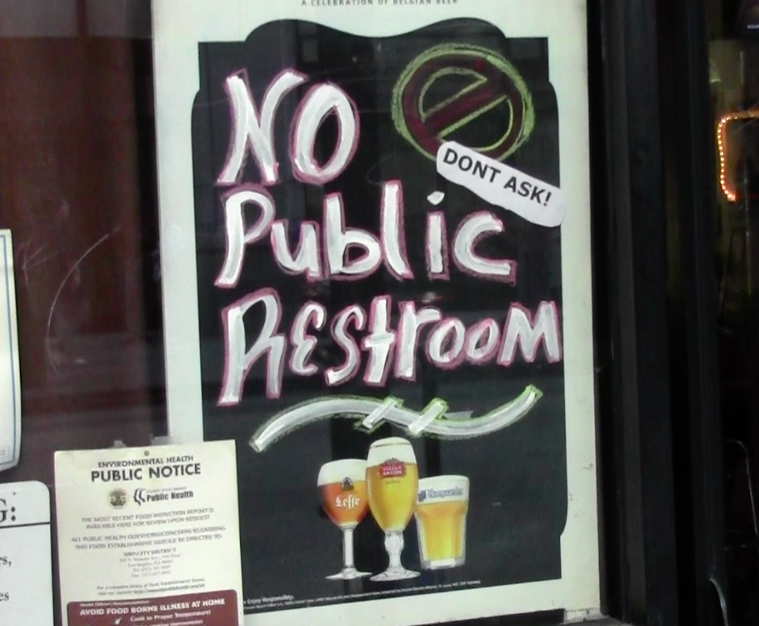

The report that came from this 2012 inspection recommended that the city install more public toilets and provide hand washing stations with soap to mitigate health risks. The shortage of public toilets, though, has not ben addressed, leaving people—homeless and otherwise—few appropriate options when it comes time to answer nature’s call.

Stevens said that when it comes to issues with the homeless downtown, public health officials typically focus on more common, “injurious” risk factors associated with congested, urban areas, like the danger of being hit by a car. Homeless advocates, however, argue that addressing the lack of sanitary bathroom access is key to the health of the community.

The World Health Organization recommends a minimum of 1 toilet per 25 users to maintain a sanitary environment. Taking into account only the homeless, who have no option besides public restrooms, there are between 8,000-11,000 people living downtown. By WHO’s recommendation, there should be about 400 toilets; there are fewer than two dozen available around the clock.

A major point of pushback when it comes to installing additional facilities is the concern that they’ll be misused. Bryson said the potential for people to use public bathrooms as drug dens or “makeshift brothels” is a deterrent for cities to install them and factors into where they’re willing to locate them.

Chloe Blalock, a program coordinator with Homeless Healthcare Los Angeles, countered that mentality with the argument that people who want to engage in prostitution and drug abuse will find a place to do so whether or not the bathrooms are there. She suggested another option for easing that concern.

“If you’re worried about people doing drugs in an inappropriate space, give them an appropriate space to do it,” she said, suggesting that the city consider setting up a safe injection site—a clean space where people can use intravenous drugs without fear of arrest— rather than making bathroom access the casualty of an unrelated issue.

City planners in Portland, Oregon addressed concerns of misuse by designing a public toilet with an open lattice on the top and bottom foot of each wall. The open design is meant to allow passing police or security to see if multiple people are inside together, and to discourage people from feeling comfortable enough to stay longer than necessary.

This design, dubbed the Portland Loo, has gained national attention for its success in Portland, and has been purchased by a number of cities, San Diego among them. The Loos are single-stall and cost about $90,000 each, not including installation.

In a proposed budget for homeless resources drafted earlier this year, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti called for $1 million to be allocated to establish “regional centers where people can shower and do laundry.” The $13 million budget didn’t make any specific mention of earmarking money to improve access to public toilets.

“It impacts everybody when there’s a lack of public restrooms,” said Michael Stoops, director of community organizing for the National Coalition for the Homeless. “We have to make our downtowns livable. This issue needs to be tackled right away.”