Think Out Loud

20-year-old cellist Kiernan Weggler shares her thoughts on generosity and privilege.

A snapshot of the Downtown Financial District's South Flower Street - a buzzing reflection of its people.

Hordes of people trickle over crosswalks and filter into office buildings, restaurants and shopping centers. Some rush to work. Others stroll with their corgis on leash. Still, there are others who call the pavement "home." The culture of the district is born out of their unlikely coexistence. See the first installation of this project here.

Explore some of the places & faces of the district below.

20-year-old cellist Kiernan Weggler shares her thoughts on generosity and privilege.

A sea of cars hurdle under the 110 Freeway overpass, which hugs the western border of the Financial District.

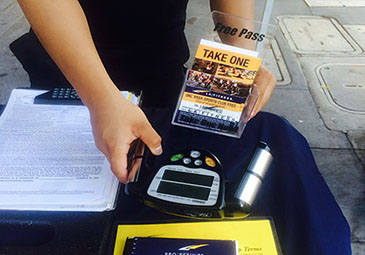

LA Fitness instructor Juan Flores hails down pedestrians to market gym memberships.

Juan Flores organizes pamphlets beneath a tent across the street from the 7th Street metro station.

The metro station at 7th Street is a majestic fusion of architectural mastery and art installations.

Part-time DJ A.J. Mueller rides the escalator to the second floor of the FIGat7th Shopping Center.

Pedestrians scramble onto the sidewalk at 7th Street toward the Ernst & Young building.

Elston Richard Truchanovich – "Truck" for short – sat on a rickety wooden step stool just a few paces south of the corner of 7th Street and Flower Street in the heart of Downtown L.A., hunched over a slab of partly tattered poster board. Scribbling in a frenzied back-and-forth gesture in Sharpie, he squinted noticeably despite a pair of heavily duct-taped, Harry Potter look-a-like glasses peeking from beneath the tufts of bristly silver hair sprouting from crown of his head (an accessory that, Truck admitted, serves little optical benefit anymore, but has nonetheless become a sort of trademark panache). He lifted his head to reveal one of two signs that read: PLEASE HELP HOMELESS VETERAN.

"This weather's got my posters all f****ed up," Truck held the board upright and sighed, part-amused and part-earnest. "I tried to cover it with tape so the paper would be protected from the rain and wind and stuff. But you know what happened? Some water seeped through, smudged all the letters, and now I can’t even fix 'em right because of all the damn tape!"

Truck has been homeless in the Downtown L.A. area for what he remembers as 10 or 15 years, though he has recently made this particular square of sidewalk space his temporary home. He is one of many displaced individuals lining the streets of the Financial District—which exists under the neighboring shadow of Skid Row—though the issue of homelessness permeates all corners of L.A. Earlier this year, a report by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority revealed a growing incidence of homelessness in the city – the tally reached about 26,000 people, charting a 12 percent increase since 2013.

And while federal initiatives as well as local policies have been working to actively combat the surge in numbers, people like Truck seek day-to-day support from the community surrounding them. Directly adjacent to Truck's stomping ground is Skid Row, where the Los Angeles Mission operates as a sort of Mecca of shelters. The Christian-run organization provides both short- and long-term housing and rehabilitation services to "people and families in need," though this predominantly materializes as homeless individuals, addicts and their families.

But shelters like the Mission seem to falter in one area: human connection. "[The shelter administrators] pretend to care about you, but they really don't," Truck said plainly. "They just need you to depend on them so that they can continue to function."

Truck has shouldered the burden of this kind of systemic apathy toward the homeless not only during his short-lived shelter stints, but also during routine interactions with pedestrians – interactions which, given the logistical parameters of homelessness, infuse every fragment of his life. This is why, instead of relying on public resources, Truck prefers to garner tidbits of support from the surrounding community.

Gauging the nature of these interactions beforehand is wrought with uncertainty, mainly because the pedestrians' responses are often clouded by widely accepted ideas of what it means to be homeless. 20-year-old music instructor and aspiring professional cellist Kiernan Weggler—between gulps of a large green tea from the Coffee Bean on the street corner opposite Truck's – believes people have been socialized to assume the worst of the homeless.

"I think that people associate the homeless with drug addicts, alcoholics, people that will not use the money that they give them to feed themselves, but to feed their addictions. And the possibility of that is reason enough for them to just walk away," she said. "It's like, we see that someone doesn't have money and automatically stop caring about them."

Tucked into a bustling network of restaurants and office buildings, Truck described his post-up as a "prime location" for panhandling. His latest sustainable olive branch is Wokcano, an Asian fusion restaurant/lounge conglomerate with a four-star rating and a modish interior – despite flaunting a tinge of DTLA's characteristically bourgeois aesthetic. The restaurant's exterior wall sits just a few meters from Truck's space on the sidewalk, and the employees often bring him leftover food during meal times. He attributed this compassion to the employees' willingness to view him as a person, instead of a homeless person.

The exterior wall of Wokcano nearest to Truck's sidewalk space, at the corner of 7th Street and Flower Street. (Emily Mae Czachor/Annenberg Media Center)

"Once [the restaurant employees] got to know me, they realized I was a real person," Truck said. "When you take the time to talk to somebody, learn their name, it humanizes them for you."

Daniel Atkins, a recent college graduate from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, has been a server at Wokcano for nearly three months. He said that most of the restaurant's employees are familiar with Truck, even if they do not directly converse with him.

"He seems like a nice dude," Atkins said. "He always says 'hello' to me whenever I pass by him. Never really asks for money. Sometimes he asks if there's any food left over in the kitchen, and we don't mind giving that to him. I know I don't, at least. Why would I?"

Hailing from a rural town, Atkins had not been exposed to homelessness, particularly the acutely conspicuous kind of homelessness that exists in a sprawling urban city like L.A. While lack of familiarity often seems to correlate with fear or a learned sense of superiority, Atkins said he felt the opposite. He chalked up the dismissive behavior he sees as "just one of those L.A. things."

"It's one thing if there's a guy on the street and he's yelling at me or being aggressive. Then I'll walk away. But that guy," he said, gesturing toward Truck. "I mean, yes, he's always going to accept cash or food. But it really seems like he just wants to ask you about your day. He could literally talk to someone for hours. And that's pretty cool to see."

It proves difficult, though, for many passersby to approach Truck with Atkins' mindset. Particularly during the midday lunch-hour rush, pedestrians sped past Truck from every direction. But, despite his glaring signs and even-toned requests for "spare change," hardly anyone paused to acknowledge him, or to offer him a donation.

But Truck does not allow their reactions to agitate him. His experience serving as a U.S. Navy operations specialist (O.S.) in the 1980s colored his lasting belief in the paramount importance of freedom and autonomy in personal decision-making – even if that decision means a person decides not to scrimp on a would-be handout, he believes it is legitimate.

"If [the passersby] don't want to offer me anything, I get that. That's their choice. That's their freedom," he said. "But being out here so long, watching everyone, it really makes you wonder: what do they think of me? They think I'm on drugs, probably."

Studies by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration estimate that approximately 38 percent of homeless people are dependent on alcohol, while an additional 26 percent abuse other drugs. Their reports indicate that these two variables – addiction and homelessness – are actually dangerously interdependent, with addiction causing homelessness and homelessness causing addiction. Truck has experienced firsthand the brunt of this cycle of street drug culture.

"People who have been living out here for a while, especially younger people," Truck said. "They're cold or they're tired or they're feeling hopeless and they fall in with the wrong people. Then, all of a sudden, they get their first taste of whatever [drug] it is, and they can't get enough. Makes 'em crazy."

But Truck's disposition seems fundamentally different from others in his situation. He waved away a young woman's cup of Starbucks coffee when she offered it ("No, no. That's yours."), and laid one of his posters flat on the pavement when she knelt to speak with him ("For your knees.").

Weggler, unfazed by the prospect of a compassionate homeless man, explained her acute propensity for making an effort to interact with the homeless. As a Los Angeles native and a working musician, Weggler has traversed the city to attend classes at the California Institute of the Arts as well as to perform on the cello at various gigs – in early October, she played at the inaugural live broadcasting of the Latin American Music Awards. Weggler is certainly a talent; her effortless and seemingly intrinsic dexterity on an instrument whose robustness alone seems overwhelming will likely pave the way toward an eventual career. But, for now, just as her Ramen-noodle-eating, public-bus-riding college counterparts, Weggler shrugged matter-of-factly, "I'm broke." And while she is sympathetic to the idea that offering money to a stranger when you are personally in some degree of a financial bind, she also both recognized and emphasized the stark disparity between "broke" and "homeless."

"If someone has less than me, I always give them money," she said. "Because I know that if I really needed it, there are people in my life who I could ask for money or for support. I could reach out to my family or my friends. Some people don't have that."

Not only does Truck rely on the semi-transient civilian community perpetually trampling through his dwelling place, he actually thrives off of it. He believes his circumstances have enlightened him, and he demonstrates a pure, unadulterated kind of peacefulness when discussing his circumstances.

"Think about it this way: if I wasn't homeless, wouldn't I get to sit here every day, always meeting new people. I wouldn't get to have Chinese food [gestures toward Wokcano] one night and Mexican food [gestures toward Qudoba across the street] the next," Truck said. "This life is always full of things to appreciate. You just gotta find 'em."

"There's a moment when [people walking past] see me," Truck said. "That's the window. After that, there's only a couple seconds to catch their attention before they decide to either keep moving, or help me out." On a Tuesday, November 17, an observational study was conducted informally in an attempt to grapple with this behavioral pattern. During a 30-minute period between roughly 12 and 12:30 p.m., the reactions of pedestrians to Truck and his "PLEASE HELP" signs were evaluated based on: gender and approximate age, whether or not they discernibly saw Truck and then averted their eyes, whether or not they offered a monetary donation and, if so, how much they offered.

The findings of these observations largely substantiate Truck's earlier claims regarding the sweeping lack of enthusiasm that people demonstrate toward panhandlers.

There's a fairly robust gap between the 65 percent of people observed as noticing Truck's presence (i.e. making eye contact, turning heads, visibly hurrying past, gripping their purses, etc.) and the 7 percent who decided to offer him money.

This correlation begs a series of questions: What causes a person to react with this kind of apathy? Is it reflective of a socialized behavior? Or an internal rationale? Over the course of 2 weeks, 100 people (selected at random) were surveyed across the lower financial district regarding their feelings toward panhandlers and the homeless.

Below is a condensed visual representation of their responses to the question:

From shoddy infrastructural dilemmas to community gathering locales, these projects explore the distinctive experiences of Los Angeles residents.

Where should you park when in the financial district of Downtown Los Angeles? With options varying from street parking to lots to garages, you may feel overwhelmed. It's time to learn how garages and lots charge so much, and which option fits your lifestyle best.

The Los Angeles Public Library is a central hub for the gathering of many cultures. In a given year, the library has about 2 million visitors and daily events year-round.

Bunker Hill is alive with the sound of music: the personal meanings behind the universal language.