A River Runs

The relationship Los Angeles has with its river

Water flows. Birds swoop. Fish swim. Bees buzz. Grass sways. Along the river bank a tarp flaps in the breeze, a man asleep beneath it. A train thunders by. Car horns blare. Smog settles, blocking the sun.

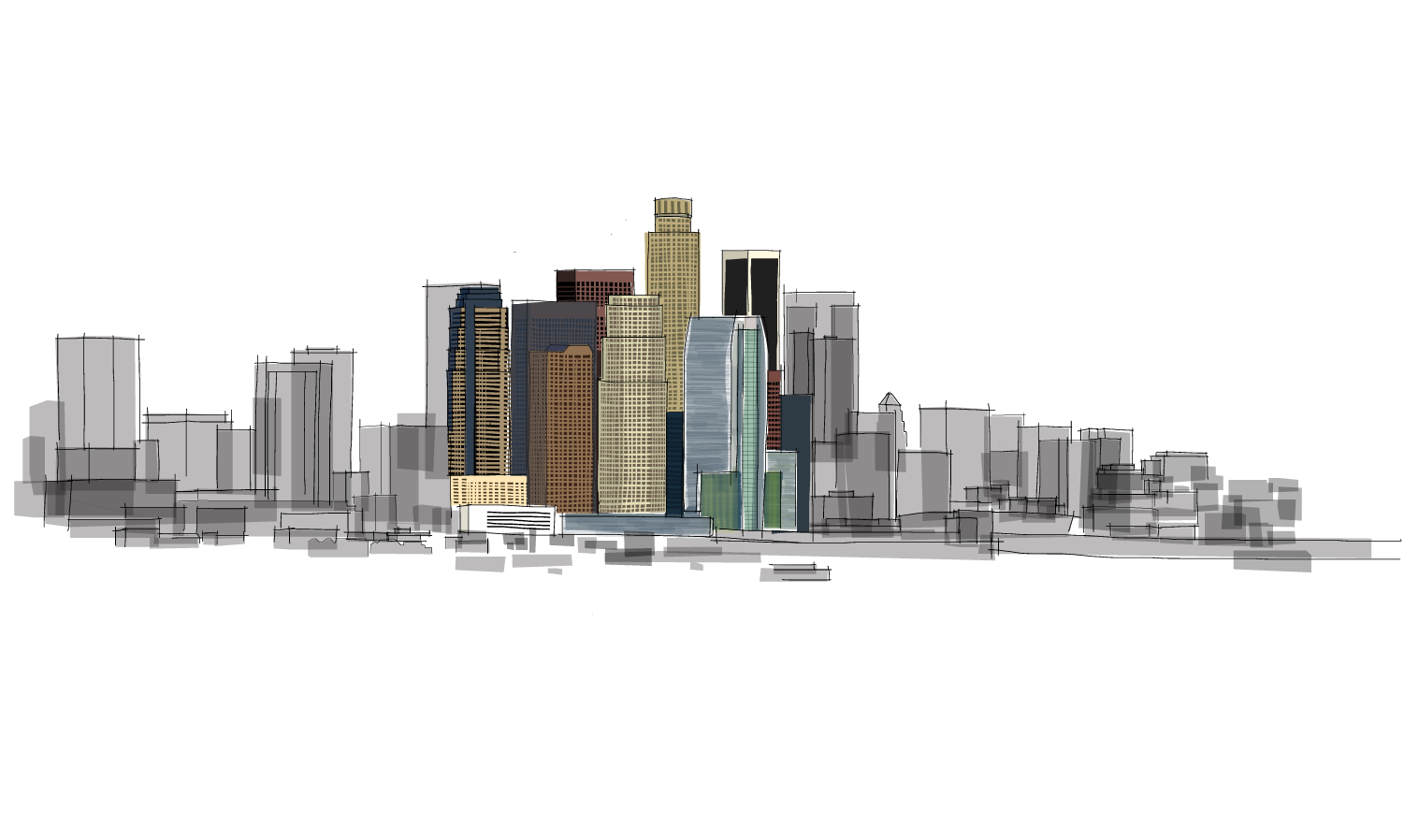

A river runs through Los Angeles. It is bursting with life, just as the city is, yet it is removed from the Angeleno experience.

Known for its identity crisis, which is in itself the city's identity, L.A. is divided by a 51-mile waterway that also suffers from a crisis of identity. The L.A. River is unlike any other, as it so closely resembles the metropolitan area it resides in. Both the city and the river are cast in concrete. Both the city and the river have a shaky past, a complicated present. Both have an uncertain future.

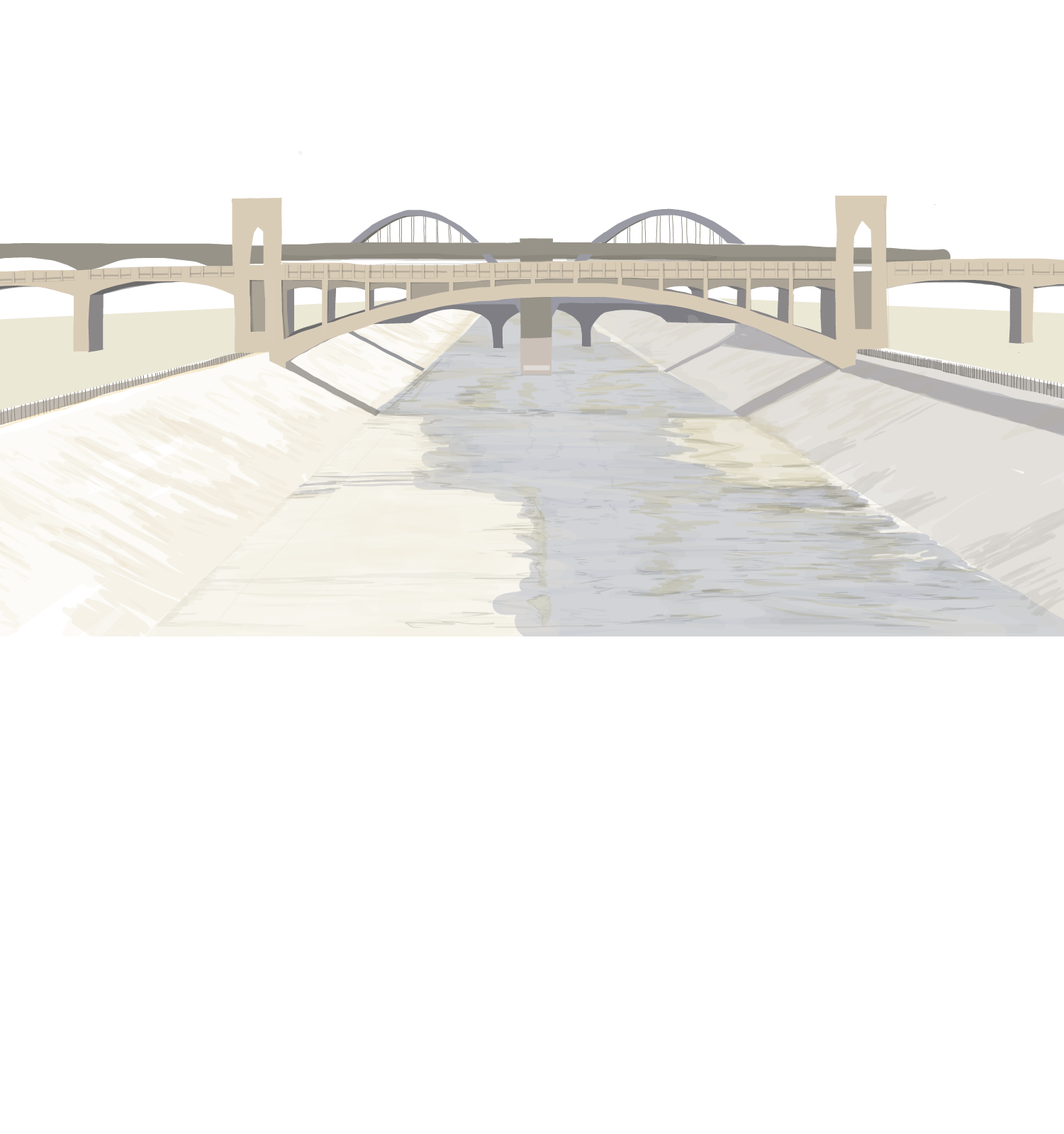

Beginning in 1938, the L.A. River underwent a transformation from natural water feature to engineered waterway. By 1960 the river bed and bank were encased in concrete, with only a few miles of the river bed maintaining a more 'natural' unpaved pebble bottom. The hope was to standardize the river's size and flow, protecting the city from frequent flooding.

In recent years the city has realized the potential for this engineered waterway to become a river once more, as restoration plans look to introduce new parks, paths and other recreational opportunities.

Landscape architect and urban designer, Ben Feldmann, has worked on restoration plans for the river. He said the fact that it is even called a "river" has been a big step in shifting the views people have of this urban space.

"The L.A. River was channelized by the Army Corps [of Engineers]," Feldmann said. "They described it as a 'floodway' and there was actually a huge movement in the last 10 years to have the L.A. River be known as the L.A. River and not this 'floodway' condition, or this constructed thing."

Not surprisingly, the river's transformation impacted Angelenos' understanding of their city's water feature. Many don't even know a river runs through the metropolitan area, let alone that it has some thriving habitats along it. It's easy to drive over the river and think of it as just another road or freeway, according to Lila Higgins, manager of Citizen Science and Live Animals at the Natural History Museum. Higgins hosts tours of the river in her free time and has dealt with such misperceptions on her outings.

They don't know it's a river or they don't acknowledge that it's a river. — Lila Higgins

"They don't know it's a river or they don't acknowledge that it's a river." Higgins said. "Then if they do know these things, they have these stereotypes: 'Oh, that's really dirty, that's where all the homeless people are, it's totally polluted, and why would I go there?'"

While some stereotypes are fitting — litter can be found scattered off of bike paths, homeless camps are infrequent but still present — efforts are being made to revitalize the river. However, in this revitalization, it is still difficult to convey changes to the public as the river is rather secluded in most places.

Steep concrete banks limit access, along with fencing around pathways. It has only been in recent years that neighborhoods have opened themselves to river access points. Those who do make the effort to explore the river will find themselves navigating unsteady boulders or pathless banks.

"Keeping people away from the river, that's what creates this perception that there's nothing there. We have, as a culture, as a society taken a lot of effort to keep people away from the river," Eric Stein, senior scientist at the Southern California Research Water Project, said.

With projects already underway restoring habitat along the river and planning recreational outings, there is a movement to open access. The master plan for revitalization of the river includes creation of park spaces and extended trails. Nearly 600 acres will be restored along the river, increasing habitat by 104 percent, within L.A. County.

There are already different types of tours to give people the opportunity to experience the river — from kayaking to cycling, bird watching to photography. Higgins herself leads tours that help introduce Angelenos to the L.A. River.

"When they come with me and meet the river it's like a first handshake," she said. "Bringing them down and being close to the river and seeing the birds, the wildlife, the fish, the water and hearing the water, just taking that moment, that kind of does it for them."

Many Angelenos would be surprised to know that there are birds, fish, wildlife and plenty of plants growing in the concrete river. There is a diversity to life along the river just as there is a diversity to the people of L.A. In a single river habitat, flora and fauna — and a few homeless — find home. The number of bird species alone found in and around Los Angeles is nearly 500, with many migratory birds stopping for a visit.

"A lot of bird communities still get use out of the river," Stein said. "Wherever you find those pockets of habitat, then things can move in and live there. We're close enough to the coast and we're close enough to natural areas up and down the coast that migratory birds they'll find those spots."

The hope is that through revitalization of green spaces along the river, there may be more opportunity for wildlife to thrive in this urban environment.

The original purpose of channelizing the river to protect land and manage flooding has shifted over the years. It's less of controlling, and more of connecting the river to the people, to L.A. Feldmann said the goal is to reconceptualize what the Army Corps' intention was, to turn it around to understanding the river's purpose rather than forcing it to serve a different one.

"We need a river designed for its urban context, that has elements or capacity for improving the ecology, for creating habitat," Feldmann said. "Ultimately we're not going to end up with a naturalized condition, we're going to come up with more of a hybrid condition that blends good engineering with sound environmental and good river ecology principles bound to it."

Plans to restructure the river are also focused on connection of the river to L.A., and its residents. This will, hopefully, help Angelenos, and visitors to the city, see the river as a feature of L.A. and make use of the space. Given the current state of the natural world — climate change, endangered species, fossil fuel consumption, pollution, etc. — it is vitally important for people to see nature, to understand it.

If people don't get that connection to the river, then the next

generation that comes along is going to care even less. — Eric Stein

"If people don't get that connection to the river, then the next generation that comes along is going to care even less," Stein said. "The argument for restoring urban rivers is that people live in cities, and if they don't get that connection when they're young it's going to be harder to get it when they're older."

L.A. has 527 miles of freeway. City planners, environmentalists and volunteers hope that drivers will get off the freeway and find their way to the urban green spaces being developed or restored along the river. Higgins said it's about environmentalism, about health, and about play.

"If the river becomes like this urban greenway, this urban parkway, through one of the largest urban conglomerations in the world, it could really transform the way children grow up in the city and also for adults, places for adults to play," she said. "It's just as important for adults to get places for respite, ride their bikes, experiencing nature, bird watching in the morning."

"I think it could drastically change life in our city."

generation that comes along is going to care even less. — Eric Stein

by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Kacey Deamer

by Kacey Deamer by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Kacey Deamer

by Kacey Deamer by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Kacey Deamer

by Kacey Deamer by Kacey Deamer

by Kacey Deamer by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Kacey Deamer

by Kacey Deamer by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Lois Lee

by Lois Lee by Kacey Deamer

by Kacey Deamer